Step Eight: Your Testimony

What Not to Say, What to Say and How You Say It.

This section is by no means a detailed essay on testifying, but rather just some general rules. (Our online video course offers detailed instructions about testifying.)

Rule Number One: Think Before Talking. Don’t utter a word during direct or cross-examination until you decide what you are going to say … and then give it one more moment, to double-check yourself. This rule applies whether your lawyer is the first to ask you questions or whether it is opposing counsel.

Under normal circumstances, and especially (normally) on your cross-examination, the less you say, the better. If you can answer, “yes,” or “no,” or “I don’t recall,” that’s great. If your answer is one of these, then answer to the lawyer. If you have to explain an answer or relay a group of facts in a brief monologue, then your audience is the arbitrator(s) or the judge in a bench trial (a courtroom trial without a jury). If there is a jury and you need to explain your answer or relay a factual story, then the jurors are your audience.

However — and this is extremely important — if you must explain something (what I call giving a "Story Answer") then make sure you know exactly where you're going with that answer before you utter a word. If you just start talking without knowing your precise destination, whether you are on direct or cross-examination, you are walking toward the edge of a cliff — and there is no handrail! If there is one surefire way to get yourself in trouble on the stand, it’s talking without a specific destination. Before you utter your first phrase, make sure you know what your last phrase will be.

Answers other than “yes” or “no” or versions of “I can’t recall" are very slippery slopes and are the primary types of answers that get witnesses in trouble. So. let me explain exactly why I call these Story Answers rather than “explanations.”

A properly crafted story has a Beginning, a Middle and an Ending. No skilled storyteller starts a story without knowing exactly where the story will end in order to deliver the maximum impact on the listener.

Explanations do not have any specific structure. Often we hear people explain something to us, and at the end of that explanation, that person continues by explaining the same thing (again) in a different way. This is how, as a witness, you can back yourself into a linguistic, legalistic corner without knowing it. It is exactly what the opposing lawyer wants you to do.

When your lawyer is preparing you for testifying, she will have a good idea what the most salient questions that opposing counsel will ask you. Your work with this handbook will help to guide you and your lawyer toward those questions and answers, and prior to your testimony you will know how you will answer the majority of the most salient questions opposing counsel will ask you.

Then, during your testimony, when the anticipated questions arise that require not just a “yes” or “no” or an “I don’t know,” but rather a Story Answer, you will simply tell your story – Beginning, Middle and End … and shut up. If opposing counsel wants to know more, then he needs to ask you another question. Your job is to answer the question, not to try to figure out whether or not opposing counsel fully understands your answer.

Inevitably, opposing counsel will ask you questions that neither you nor your lawyer anticipated. If, on the spot, you determine that a specific question requires not just a “yes” or “no” but rather a Story Answer … then STOP, THINK, and CRAFT the Beginning, Middle and End to your story. For example: BEGINNING - “I heard a crash.” MIDDLE – “I ran into the lobby.” ENDING – “And I saw Jim with a baseball bat in his hand and the smashed vase on the floor.”

When CRAFTING a story in a short period of time, the key is, “Keep It Simple Stupid.” We don’t need to hear that you were wearing new shoes and you almost slipped as you ran toward the lobby; that Jim was wearing a blue blazer that looked dusty and a bit unfashionable; and that the vase was Waterford crystal in the Kildare pattern. If you didn’t anticipate the question, just provide the most important facts.

You Are Not Your Advocate

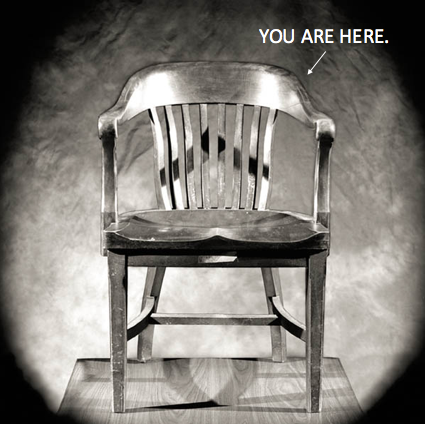

You are there to provide the facts. That is your role. You are not there to advocate for your position; that is your lawyer’s job. Your job is to be as courteous and polite to opposing counsel as you are to your lawyer. You are not there to argue. If the photo below is you and opposing counsel when you are testifying, you will lose. She understands how to maneuver in these waters; you don’t.

Whether it is your lawyer or opposing counsel asking questions, do not speculate. If you saw something, if you did something or if you heard something from the “horse’s mouth,” then you can say what you saw, what you did, or what you heard – unless what you heard falls in the category of hearsay evidence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hearsay Have your lawyer explain exactly what hearsay evidence is and what the exceptions to hearsay are. [The best book on hearsay and its exceptions (that I’ve ever read) is G. Michael Finner’s The Hearsay Rule.]

Here’s what you need to remember: If you didn’t see it or touch it or hear it, you can’t testify to it.

Again, during your testimony, you should never, ever speculate, or say what you think might have happened, or what someone might have been thinking, or what they might have said or done. If you are being asked about something that happened a long time ago, if you do not remember exactly what happened, say you can’t remember.

Recently, a legal team and I had a perfectly nice client who had such a desire to be helpful, that he allowed opposing counsel to put words in his mouth:

OPPOSING COUNSEL: You probably would have called him after receiving that email, right?

OUR CLIENT: Right.

Wrong! His job was not to be helpful to opposing counsel. His job — and yours — is to tell the truth.

The same client, when answering questions, would say things like, “What I probably would have done, is …”

No, no, no, no, no. We don’t want to hear what you probably would have done or said. We only want to hear what you remember saying and what you remember doing.

Now, this was a client who the lawyers and I spent many days prepping. However, it is very important to note, that this client never did his homework. He never did the homework that this handbook is guiding you to do. If you don’t do your homework, you should not be surprised when you fail the test. As we say over and over, “Anger is an expensive emotion." But just as expensive, is procrastination or laziness when it comes to the work you need to do on your own when getting ready for trial. You can’t cram, two days before your trial and expect to receive flying colors and prevail.

During your testimony, stay away from absolutes. If you are not absolutely certain about something, use the phrase, “To the best of my recollection.…” But that does not mean you should speculate. [Have we said that enough times?] If you aren’t pretty darn sure that you remember some fairly specific details about something, simply say, “I really don’t recall,” or “I just don’t remember.”

TESTIFYING WITH DOCUMENTS

In the scenario below, you are the owner a financial services company.

You have been sued by an employee who you fired. You, our client (and witness), are on the stand being cross-examined by opposing counsel.

THE WRONG WAY TO TESTIFY

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Have you seen this document before?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Yes. It’s an email that Sam sent me just after we let him go. He was complaining about how he was treated when he worked with us. Sam’s a complainer.

Right, then Wrong, Wrong and Wrong: The lawyer asked you if you had seen the document before. You answered, “Yes.” But you didn’t stop there — and you should have. He didn’t ask what the document was. And he didn’t ask about the information on the document. Also, you characterized Sam in a negative way, which is something you should almost never do. Your job is to present the facts and allow the judge, jury or arbitrator(s) to decide if Sam sounds like a complainer. It's their opinions that matter, not yours.

If your lawyer or opposing counsel hands you a document – look at it. If he or she is asking specific questions about the document, and if you haven’t read it recently, read it. Make sure you know exactly what the document says before you answer questions about it. It is absolutely fine for you to say to opposing counsel or your lawyer, “May I take a moment to read this?”

Often, opposing counsel will ask you to refer to one sentence of a document and comment on that sentence or a particular phrase or word before you've read the document.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Could you take a look at the first sentence of the second paragraph for us?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Yes. May I take a moment to read the first paragraph first?

Now opposing counsel may reply to this, something like:

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Yes you may, but first I just want to ask you about that one sentence.

CLIENT/WITNESS: I’d like to read the first paragraph first, please.

[Let’s move on to other questions about the document.]

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Do you see the date on the email?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Yes. January 3rd, 2014. Just over two years ago.

Right. Then Wrong and Wrong. Just answer the question that he asked – and shut up. If he wants more information, let him ask for it.

[Let’s move on.]

OPPOSING COUNSEL: What were you thinking when you read this?

CLIENT/WITNESS: I was thinking about all the complaints that Sam had over the years. I was just kind of adding them up. At that point, I was absolutely certain that he was going to sue us, which is the sort of person he is. He’s vindictive.

Wrong, Wrong, Wrong, Wrong and Wrong: First of all, you read the email two years ago; how on earth could you remember exactly what you were thinking? You are just guessing, and that makes you sound like you are not credible. In the second sentence, you are again guessing, and you are speculating; you could not have been “absolutely certain” that he was going to sue you until he did.

Furthermore even if you do clearly remember speculating that at the time, it doesn’t matter. If you had changed, “I was absolutely certain,” to “I thought he might sue us,” this would have made you sound more credible.

In legalese, “credible” is a term of art. If a witness confidently relays facts and appears to be a source of reliable information, then he or she is deemed credible.

In the last part of your testimony above ("He's vindictive."), you are again characterizing Sam in a negative way. Let me repeat, your job is to present the facts and allow those judging your case to decide if Sam is a complainer and vindictive.

If you are the client testifying, whether you are the plaintiff or defendant, we don’t want to hear you characterizing your opponent negatively. Hopefully, you will have other witnesses who work at your company who can testify to specific examples of Sam complaining and behaving vindictively. But it is okay for them to characterize Sam’s behavior because they are not the person Sam is suing. They are far enough removed from the battle to be viewed as credible. They can sometimes offer opinions and those opinions will be viewed favorably if they are specific and particularly if your witness can cite specific incidents of Sam’s bad behavior.

If you do not have witnesses who can offer such testimony, then you need to wait for your lawyer to ask you about Sam during your direct testimony.

YOUR LAWYER: Would you say Sam was an easy employee to work with?

CLIENT/WITNESS: No.

YOUR LAWYER: Why not?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Well, Sam was a great employee in many ways, but we could never seem to make him happy. The building was always too hot for him, he told me repeatedly that didn’t like the view from his office and asked if he could switch offices with Jim Barnes. We bought him three different office chairs and none of them suited him. And he regularly came to me demanding that I fire an employee who he considered unprofessional, even if they didn’t work in his department.

YOUR LAWYER: Can you give me a specific example of someone he tried to get you to fire?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Yes. Three weeks before we let Sam go, he told me I should fire Jim Barnes who I had just promoted to a position that Sam wanted.

You see, of course, what you are doing here: You are simply stating facts and allowing the arbitrator, judge and/or jury to conclude that Sam was a vindictive complainer.

Additionally, what we are saying here, is that it is not simply important to state the facts as you know them. How you relay those facts – the words you use, play an extremely important role in how the facts you relay will be received by those judging you.

But even more importantly, the way you speak the words in your testimony will have a gigantic effect on how they are received and how credible, likable and trustworthy you will appear to be. In our online video course, we detail exactly what you need to be doing during your entire testimony to be judged positively. To view a 40-second clip from that particular section of our course about what you need to be doing during your testimony, go to: http://JurisPerfect.com. Click on the Handbook and go to Step Number Eight. About halfway through that section, click on the video just above “THE RIGHT WAY TO TESTIFY.”

THE RIGHT WAY TO TESTIFY

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Have you seen this document before?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Yes.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Would you identify it for us?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Yes, it’s an email from Sam to me.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: How would you characterize this email?

CLIENT/WITNESS: It was an email from Sam to me. [Note, you are not being a smart-ass here. His question is unspecific, so an unspecific answer is fine. If he wants to be more specific, let him rephrase the question or ask another question.]

OPPOSING COUNSEL: What is the date on the email?

CLIENT/WITNESS: January 3rd, 2014.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: That was two days after you fired him wasn’t it?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Yes.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: What is the email about?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Sam says here (reading email), “I was never treated well by you or anyone at Jones Financial.”

OPPOSING COUNSEL: How did you feel when you read that?

CLIENT/WITNESS: I don’t remember.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: You don’t remember?

CLIENT/WITNESS: No.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Why not?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Well, that was over two years ago.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: So?

CLIENT/WITNESS: So, I don’t remember how I felt when I read that two years ago.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Well, didn’t it make you feel bad?

CLIENT/WITNESS: I really couldn’t say. I don’t remember.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Well, wouldn’t it be fair to say that any employer would feel bad if a former employee said he was never treated well by the owner or anyone at the company?

CLIENT/WITNESS: I really can’t speak for all employers.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: You just said it didn’t make you feel bad. Did it make you feel good to read that?

CLIENT/WITNESS: First of all, I didn’t say I didn’t feel bad, I said I don’t remember how I felt when I read this.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Well, did it make you feel good when you read that?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Like I said, it was two years ago. I don’t remember how it made me feel at the time.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: How does it make you feel now?

CLIENT/WITNESS: I’m just rereading an email I received two years ago.

OPPOSING COUNSEL: Well does it make you feel good or bad?

CLIENT/WITNESS: Neither really. It’s just an email from a former employee.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Deposition Testimony Prior to Trial

This is a really simple instruction: If you were deposed, prior to your mediation, arbitration or trial in court, read your deposition – over and over and over. Your lawyer will give you specific instructions on what to do if you made factual mistakes during your deposition, and how you can mitigate those mistakes when you testify in court or in an arbitration.

Unclear and Warning Flag Questions

If your lawyer or opposing counsel asks you a question that you don’t understand, tell him that you don’t understand the question. If he simply asks you the same question again, say:

WITNESS: I apologize. I still don’t understand the question. Would you mind rephrasing it?

Here’s a good rule of thumb that I tell every client or witness I prep: “Once you hear a question, you will know you are ready to answer it if you feel like you could turn to someone and ask him or her that same question."

Warning Flag Questions from Opposing Counsel

Any question that starts with the phrase:

“Would it be fair to say that …”

or

“Wouldn’t you agree that …”

or

“Now in your previous testimony …”

or

“You heard Mr. Jones testify that …”

If you hear any of these phrases, pay very close attention to the rest of the question and think hard about your answer before you say a word.

To varying degrees, these are known as Leading Questions, which are permitted on cross-examinations by opposing counsel, but not permitted on direct examinations from your lawyer. However, if your lawyer does ask you questions like these and if opposing counsel does not object to the court (the judge), these are Softball Questions right down the middle of the plate. Your lawyer expects you to hit them out of the park. Most likely you and your lawyer will have worked on these types of questions and answers quite a bit.

Our online course goes into great detail regarding what you need to do and say during your testimony, but should you choose not to view that course, make sure that you make yourself completely available to work on your direct and cross-examination testimony with your lawyer and/or legal team. Yes, your hours working with your lawyer are expensive. But proper preparation for your testimony will be some of the wisest dollars you will every spend.

Testifying is hard because it is unlike your normal, everyday communications. It’s very easy to make mistakes, so prepare, prepare, prepare.

I have never seen a witness who was over-prepared to testify. In my opinion, there is no such thing as being over-prepared to testify.

But every single year I see clients and witness in court who have not taken the time and applied the focus they needed to, to come across as great witnesses … and it always damages their chances of prevailing. Don’t be one of those clients or witnesses.